Silvergrass

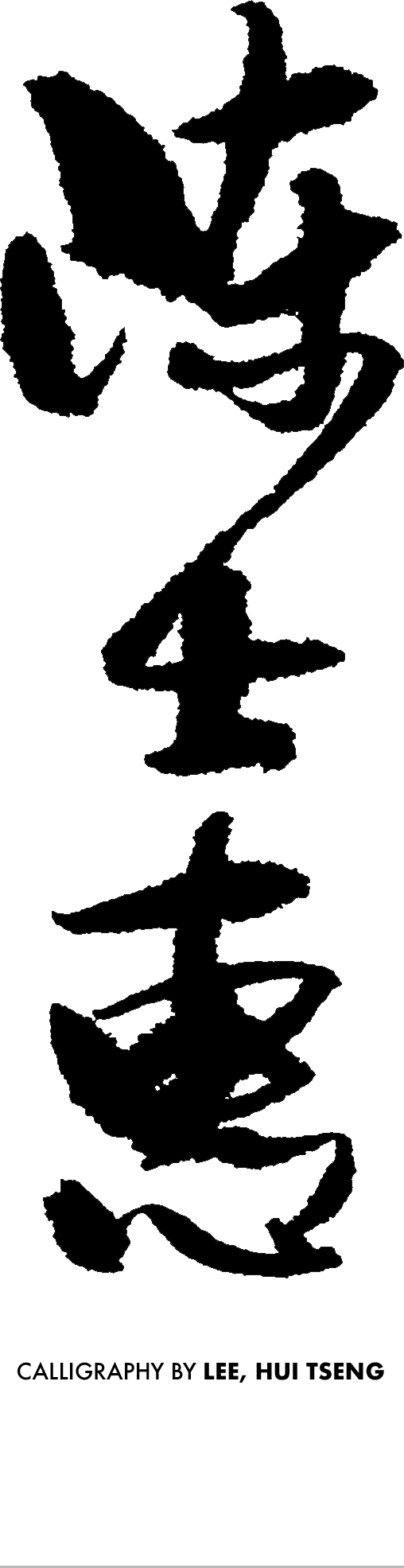

菅芒花

for Cello and Chamber Orchestra (2016), ca. 13’

for Cello and Chamber Ensemble (2017), ca. 13’

Study Score

$95

I’ve been a big fan of the Taiwanese writer, Huang Chunming for more than 30 years. Most of his works focus on the working class and have an intimate, melancholy quality, the so-called “Taiwanese flavor.”

Before I was eight, I lived with my grandmother in Ba-du, a small town outside of the big city of Taipei. As Grandmother ran a small hotel by a railroad station where trains run between Taipei and the rural area, the hotel was busy and often packed with people whose lives were filled with hardship and hard work. In the midst of their difficulties, however, these Huang Chunming-story-like people took comfort in and entertained themselves with the Taiwanese operas. Before I began my Western music training, my ears were filled with these sad Taiwanese opera melodies. Although I was unaware of its influence, as I revisited Mr. Huang’s poetry recently, I reconnected with the Taiwanese opera and the long forgotten faces of people who once lived in the Ba-du hotel. I was feeling nostalgia. It also brought some heartache, as my grandmother passed away almost 20 years ago, and her hotel has not been operating for many years. The once robust Ba-du railroad station has now become desolate, with few people lingering.

Silvergrass uses four of Mr. Huang’s poems: Silvergrass, My Vegetarian and Sutra-Incanting Grandmother, Turtle Island and Guojun Is Not Coming Home to Dinner. Typical of Mr Huang’s passion in depicting working- class and mundane daily activities, all poems share a similar duty devotion: The silvergrass' dutiful annual sweeping of the sky; the grandmother’s daily chanting and vegetarian observances; a traveler whose emotion is tied to home, who changes the counting sheep chant to words about home; and the parents who keep a seat for their child who will not return. While the first three poems are cheerful, child-like, and bring back warm memories and happiness, the last poem introduces a profound sadness. It conveys Mrs. Huang’s grief at their son’s tragic death at age 30. This poem pulled me back to reality, and I empathized with the parents. I, too, am a mother. Because of the poems’ simple and direct quality, they provided me an immediate inspiration and imagination for composing abstract music. Finally, I loosely adopted the “crying melodies” from the Taiwanese opera, and it is used most apparently in the last movement.

Silvergrass was commissioned by the National Taiwan Symphony Orchestra. In addition, there is an ensemble version written with the generous support from the Taiwanese United Fund. This work is dedicated to Huang Chunming, with admiration.

我一直喜愛黃春明的作品,是他30多年的粉絲! 春明老師的作品都有點淡淡的哀愁,我想這就是所謂的「台灣味」吧!

八歲以前, 成長在外婆八堵旅館的我是聽歌仔戲長大,不但楊麗花、葉青、廖瓊枝的曲調常縈繞我耳,也看到許多如春明老師小說中,為了討生活,臉上寫滿辛酸與無奈的小人物。外婆過世已近20年,而她白手起家、一手建立的「新生旅社」,如今已關閉多年。在半個世紀以前,外婆的旅社就位在人潮旺盛,行商必經的八堵火車站對角。隨著歲月的流逝,八堵火車站早已失去昔日榮景,行旅稀少,連我都不敢、不忍停留寸步。重讀黃春明的作品,讓我憶起那一塊已經很久沒有碰觸、甚至已經不存在的時光,它喚起了我淡淡的哀愁。

〈菅芒花 〉的四個樂章採用黃春明四首詩:〈菅芒花 〉、〈吃齋唸佛的老奶奶〉、〈龜山島〉、〈國峻不回來吃飯〉。這四首詩都有他細膩描寫日常生活點滴、小人物的堅持與無私奉獻的一貫筆法—菅芒花每年某日固定的來打掃天空、一直唸佛經吃齋的老奶奶、不斷地數著回家日子,心理掛牽故鄉的遊子、以及總是等著兒子回家吃飯的父母。前三首詩溫和親切,甚至有點童詩的味道,讓出國30多年的我,重享孩童時候的溫馨與看歌仔戲的熱鬧;而最後一首〈國峻不回來吃飯〉卻相當沉重,把身為人母的我拉回現實,感受同理心。由於這些詩直接、簡單、平易近人,在音樂的創作上,它們給予我無限的空間及豐富的想像力;而音樂方面,我則受歌仔戲的哭調啟發,並明顯的運用於最後一個樂章。

我對黃春明老師作品的感觸30年如一日: 深沉、犀利、 一萬個讚!

Text

Poems by Huang Chunming 黃春明

Translated by Tze-lan Sang

These translations were published in Chinese Literature Today 8, no. 1 (2019): 91-96

Silvergrass

Every year

The silvergrass never forgets to show up on this day

To sweep the sky

During daytime

By the brooks the silvergrass stands

Sweeping the sky blue

On tiptoes on mountaintops

it stands

Sweeping the sky high

Then it calls the sky swept blue and high

Autumn

At night

The silvergrass

stands

By the creeks

Dusting the stars bright

On tiptoes on mountaintops

Dusting the stars far

Then it names the stars it dusted bright and far

The Milky Way

An old farmer

Who makes brooms

With the sky-sweeping and star-dusting silvergrass

Goes to the city to hawk them

When the women show disbelief around him

He just tells them to take a look

Up at the sky

〈菅芒花〉

每一年的這一天,菅芒花

總不會忘記來打掃天空

白天

菅芒花站在水邊

把天空掃得藍藍的

菅芒花墊腳山巔

把天空掃得高高的

然後把這掃得

藍藍又高高的天空

取個名字叫

秋天

夜晚

菅芒花站在水邊

把星星撢得亮亮的

菅芒花墊腳山巔

把星星撢得遠遠的

然後把這撢得

亮亮又遠遠的星星

取個名字叫星空

老農夫

把掃過天空、撢過星星的菅芒花

編成一把一把的掃把

帶到城裏叫賣

當圍觀的婦女表示懷疑

老農夫就叫人抬頭看看

天空

My Vegetarian and Sutra-chanting Grandmother

Old Grandma has a Buddhist prayer hall decorated in red

Adults say it is not a place where we kids should play

The hall often overflows with Grandma’s low singing

Out wafts the hum of recitations and the sharp scent of sandalwood

Out comes the drone of incantations punctuated by the knock knock ding of the temple block and copper bell

A vegetarian, Grandma recites the sutras and performs good deeds

She says the Buddha forbids killing

That the Buddha prohibits this and that

Namo Amitabha knock knock ding

Knock knock knock knock ding

Grandma has a Buddhist prayer hall decorated all in red

Inside is a red table

On the table sits a stack of sutras bound in leather with embossed red and gold characters

When she chants, she starts at the top with the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra

And works her way down

Until she reaches the Diamond Sutra

Grandma chants

Namo Amitabha knock knock ding

Knock knock knock knock ding

When Grandma finishes chanting the Diamond Sutra

She begins all over again with the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra

She keeps incanting, working her way down

Namo Amitabha knock knock ding

〈吃齋唸佛的老奶奶〉

奶奶有一間紅紅的經堂

大人說,那不是小孩子玩耍的地方

經常早晚傳出奶奶誦經聲喃喃

誦經聲喃喃,飄出撲鼻的檀香

誦經聲喃喃,帶著木魚銅鐘喀喀鏗

喀喀喀喀鏗

奶奶吃齋唸佛勸行善

她說,佛說不許殺生

她說,佛說不許那樣和這樣

南無阿彌陀佛喀喀鏗

喀喀喀喀鏗

奶奶有一間紅紅的經堂

紅紅的經堂有一張紅紅的經案

經案上有一疊紅金燙皮的佛經

奶奶從上面的波羅蜜多經

一直唸,一直唸

一直唸到下方的金剛經

奶奶的誦經聲喃喃

南無阿彌陀佛喀喀鏗

喀喀喀喀鏗

奶奶唸完金剛經

再從頭翻開波羅蜜多經

一直唸,一直唸

南無阿彌陀佛喀喀鏗

Turtle Island

Turtle Island

Whenever this child of Lanyang takes the train to travel faraway

Whenever he gazes upon you from the distance

He can never tell whether the melancholy in the air

Belongs to you or him

Turtle Island

On the days this child of Lanyang stayed away from his hometown

A multitude of dreams would cause insomnia

He dreamt of the Turbid River

Of Typhoons Pamela and Beth

Of you, Turtle Island

The doctor in the alien city

Taught him to count sheep

One sheep, two sheep, three sheep

Four Turbid River, five typhoon

Six Turtle Island

Ah Turtle Island

Whenever this child of Lanyang takes the train home

He can never tell whether the excitement and joy in the air

Belongs to you or him

〈龜山島〉

龜山島

每當蘭陽的孩子搭火車外出

當他從車窗望著你時

總是分不清空氣中的哀愁

到底是你的,或是他的

龜山島

蘭陽的孩子在外鄉的日子

多夢是他失眠的原因

他夢見濁水溪

他夢見颱風波蜜拉,貝絲

他夢見你,龜山島

外地的醫生教他數羊

ㄧ隻羊、兩隻羊、三隻羊

四隻濁水溪、五隻颱風

六隻龜山島

龜山島

每當蘭陽的孩子搭火車回來

當他從車窗望見你時

總是分不清空氣中的喜悅

到底是你的, 或是他的

Guojun Is Not Coming Home to Dinner

Guojun, I know you are not coming home to dinner, so I ate first.

Your mom always says, wait a bit.

Because she ends up waiting too long, she loses her appetite.

That bag of rice is still full a great many days after we opened it. It even gained some weevils.

Since mom knows that you are not coming home to dinner, she no longer wants to cook.

She and the Tatung rice cooker have forgotten how many cups of water should go with a cup of rice.

Only now do I realize that mom was born to cook for you.

Now that you do not come home to dinner, she has nothing left to do.

She does not feel like doing anything, not even eating.

Guojun, it is has been a year—you have not come home to dinner.

I have stir-fried rice noodles a few times to invite your friends over.

Some of your best friends came, but Zhesheng, like you, also

no longer goes home to dinner.

Since we know you are not coming home to dinner,

we do not wait for you, nor do we talk about you.

But we will always save a seat

for you.

〈國峻不回來吃飯〉

國峻, 我知道你不回來吃晚飯,

我就先吃了,

媽媽總是說等一下,

等久了, 她就不吃了,

那包米吃了好久了, 還是那麼多,

還多了一些象鼻蟲。

媽媽知道你不回來吃飯, 她就不想燒飯了,

她和大同電鍋也都忘了, 到底多少米要加多少水?

我到今天才知道, 媽媽生下來就是為你燒飯的,

現在你不回來吃飯, 媽媽什麼事都沒了,

媽媽什麼事都不想做, 連吃飯也不想。

國峻, 一年了, 你都沒有回來吃飯

我在家炒過幾次米粉請你的好友,

來了一些你的好友, 但是哲生也跟你一樣,

他也不回家吃飯了。

我們知道你不回來吃飯;

就沒有等你, 也故意不談你,

可是你的位子永遠在那𥚃。